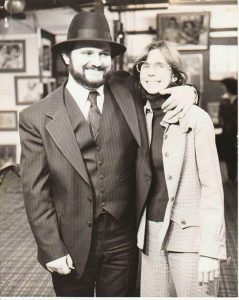

The first time I invited George Mallus (aka Yorgo the Greek, aka “Guy” from my newspaper columns) to my parents’ farm in Brimley, he thought he was on the set of The Waltons. George was a product of the city, having been born and raised in the Detroit area. He had no more idea of country life than I did of metropolitan living until I left the side road. It didn’t take me long to adjust to city life and all it had to offer. Not so with George and the countryside surrounding my childhood haunts.

George was the first Detroiter I brought home. I had no idea how he would react to the screech of an owl at night or the howl of a coyote. I thought he might run for the comfort of the city when he heard May peppers filling the night air with their endless croaking, but he was willing to take his chances so I was game. Once we turned off M-28 and hit the gravel road leading home, the dust nearly choked him. As I wheeled his Subaru Brat towards my parents’ home, he clung to his seatbelt and groaned, “Where are you taking me and why?”

It was a standard joke among my Detroit friends that I was a farm girl, but nobody really believed my stories about growing up on a farm and living without modern conveniences. For a year, George had pestered me to show him my Upper Peninsula roots. I was none too eager to accommodate his request because the farm was nothing new to me. I didn’t understand my friend’s obsession. By 1976, my parents had lived in their mobile home for eight years. The old house was abandoned, only a few Herefords grazed the fields, Dad had sold the milk cows, and farm life wasn’t what it used to be.

However, to satisfy George’s curiosity, I told him to pack a bag. We were heading North for Mother’s Day weekend. The first thing he did was buy a box of Sander’s chocolates for Mom and a bottle of Seagram’s 7 for Dad. No Greek worthy of his name ever entered a stranger’s house without bringing gifts. However, as his lungs filled with dust from the road, the poor guy thought I was trying to terminate his existence by suffocation. He was probably tempted to crack the seal on the liquor to calm his nerves.

But as soon as I turned in the driveway and the dust settled, George relaxed. He hugged Mom, shook hands with Dad, petted Dusty the dog, and got out his camera. He snapped pictures of everything and everybody. Photography was one of our hobbies, and he lost no time in documenting what he called “The Waltons.” Although the house trailer had no resemblance to the fine farmhouse belonging to the television family, it was the land that intrigued him. He couldn’t grasp the concept of owning 165 acres. No one he knew owned more than the speck of land upon which their house stood.

What was old hat to me was a novelty to George. He explored the haymow, then climbed down and entered the barn, examining each stall and cow chain hanging from a hook. For the first time in his life, he held a pitchfork, sat on a bale of hay, ran his fingers through oats in a bin, and opened a can of Bag Balm. The barn cats climbed on his lap, unafraid of the newcomer. He thought all such cats were wild, but I said nothing was wild around our farm. Kindness was as much a staple at our place as was the morning sun.

The horse barn was our next stop. He stood in stalls where our work horses had stood years before I was born. He felt the stiffness of old harnesses and reins. Next, we ducked as we entered the chicken coop because the building was low and sinking into the ground. He ran his hands along the indentations where hens had once laid their eggs or protected their chicks. He inhaled the scent of the buildings, proclaiming each one sweeter than the last.

We left the barn and walked the short distance to the house. He marveled at one room after another—the enormous kitchen, the woodbox piled high with maple and birch that never saw the inside of the stove. Mom and Dad had moved to their trailer in August of 1968 and left things as they were. George saw the table where empty water pails waited for their daily trip to the wellhouse where fresh well water was pumped into them. He lifted mesh flyswatters from their nails, swatted the air, and said he felt like he was home.

Home? Home for him was a busy street in Detroit and later a carriage house in Indian Village, a once-prosperous area with mansions lining the streets. Home was endless traffic and sirens blaring night and day. Home had nothing to do with the farmhouse kitchen where he stood. I looked away as he brushed something from his face. He asked me how I could have left something as beautiful as my homeland.

I snapped him out of his melancholy by reminding him that life in an empty house could be any way he cared to describe it. George was an artist. He saw the deserted house, the abandoned pictures still hanging on the walls, the quiet barn, and the rusting farm machinery as a rejection of a way of life. He had no concept of the hardship involved in that life. I told him to dry his tears, paint what he saw, and get over it. I said it was not my intention to depress him. He explained he wasn’t depressed, just touched by the simplicity of the first 21 years of my life. He now understood why I was the way I was. He said it all made sense to him.

Well, it didn’t make any sense to me, and I couldn’t wait to get him back to Detroit where he was a jovial character. We closed the kitchen door on my memories and his imagination and joined Mom and Dad for supper. I spent the rest of that weekend showing him the local sights and steering him clear of the old buildings on our property. On Sunday afternoon we hugged my parents, promising to return in the fall.

Once we crossed the Mackinac Bridge, George became his old self. He was Yorgo the Greek, a happy fellow who put his feelings on canvas, not on display. Eventually he painted Dad’s dog and Rochester, the parakeet he had given me that I didn’t want and had brought home to my parents. When the leaves turned in September, we drove home and delivered the painting.

George passed away seven years ago. Although I hadn’t seen him in years, I was saddened. He was a good man who accepted people as he found them. I guess there’s no better epitaph than that.