By Sharon M. Kennedy

August has a special feel to it, unmatched by any other month. The lazy dog days melt seamlessly into one another until it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins. At least, that’s the way it was when I was young. Cumulus clouds filled the sky, hay was harvested, vegetables canned, and Mom shopped for our school clothes at Montgomery Wards or J. C. Penney’s.

The 15th of August is the day Catholics celebrate the Assumption of Mary into heaven. I don’t know if the tradition continues, but when I was growing up we always went to mass to mark the occasion. But there’s another reason why that date is memorable, and it has nothing to do with religion. It has to do with Broken Horn, Mom’s favorite Hereford. I was about 12 years old and remember that day as if it were yesterday.

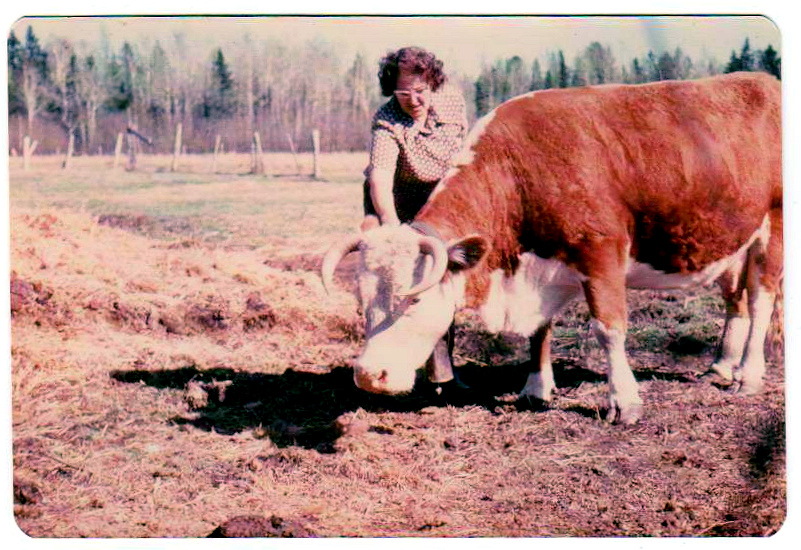

The other cows had freshened in early spring like they’re supposed to, but Broken Horn wasn’t due until August. For a week, Mom had walked down the road to the field where our Herefords were pastured during summer. She regularly checked on Broken Horn to make sure everything was okay as her due date neared. When Mom didn’t see her, she was convinced something was wrong so on the 15th our relatives rallied and helped us comb the pasture and the woods behind it where the cattle often roamed. I stayed with Mom. I don’t remember how long we walked and called the cow’s name, but the memory of what we found has stayed with me to this day.

We were walking along the stream where clover and wild Rose of Sharon grew when we entered a quiet spot where the cows liked to rest in the shade of the trees. It was cool and everything was still. There was a feeling of peace in that clearing, kind of like the way a church feels on Sunday mornings before it fills with people. Mom was a few steps ahead of me, holding branches aside so they wouldn’t fly back and hit me in the face. Red tuffs of hair were snagged on some of the branches where cows had pushed their way through. Rust-colored pine needles carpeted the forest floor. Purple wildflowers circled the area and maidenhair ferns were everywhere.

What I remember most about that day is the smell. Without warning, a gentle breeze stirred the air and brought an unpleasant odor to me. I started to complain about the stench when Mom silenced me. She strained her head to one side as if listening to something. I did likewise, but all I could hear were birds and the rustle of leaves as the breeze ran through them. Then I heard the moans.

They were getting closer but not stronger like the smell. I reached for Mom’s hand and her fingers locked with mine. We took a few more steps and then we were there, facing the sight we had hoped God would spare us. Mom dropped my hand and ran to the animals. I stood alone and watched as she cried “Broken Horn” in a voice that told me the house would be very quiet that night and there would be no going to mass.

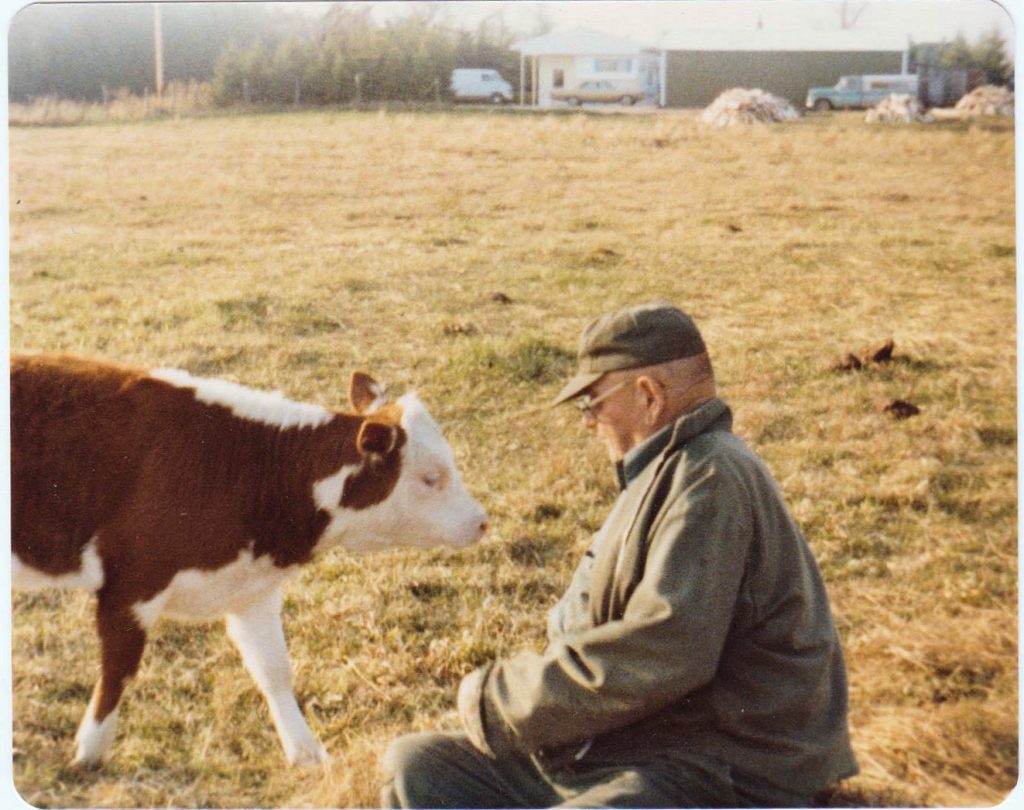

A young Precious amongst the goldenrod

A young Precious amongst the goldenrod

Mom said to get Dad, and I ran from the clearing. I remember the shrill of my whistle breaking the silence of the woods. I kept yelling for Dad, but all I heard was the echo of the whistle and my words as they bounced back to me, and all I saw was the sight in the clearing. Broken Horn’s calf, a big, beautiful blood red heifer, was next to her but she wasn’t breathing. She was dead, probably had been for days, and the crows had been feasting. Broken Horn lay on her side and didn’t stop moaning even when Mom put her arms around the cow’s neck.

If you’re like me, some scenes from your childhood are permanently etched in your mind’s eye and no matter how hard you try, you can’t remove them. There’s no “delete” button to erase the memory. Dad and my uncles buried the calf, but I didn’t stay around to see it. Somehow they managed to roll Broken Horn onto a low trailer and brought her home. Mom called the vet, but when he saw the cow he said there wasn’t much he could do for her and the kindest thing would be to put her out of her misery. I was in my playhouse when I heard the shot from Dad’s rifle.

Whenever the 15th rolls around, I remember that August day of so long ago. The field where Broken Horn’s calf died is a forest now, filled with maple and spruce trees, a few birch, and a scattering of red pines. My brother’s home is just down the road from me, nestled among the trees that overtook the pasture. The path once leading to the gate is now a driveway. The fences are gone, the beavers dammed the river so not even a stream remains, and the ground will never again grow hay.

Although I had seen dead cats and dogs, their passing didn’t bother me as much as Broken Horn’s and her calf. I cried the day we found them because I imagined Broken Horn had suffered knowing she couldn’t help her baby. She had to watch it die. Dad said the calf was probably stillborn, but I didn’t believe that. I figured getting born was just too much for it and it gave up before ever trying to live. I thought maybe Broken Horn had tried to coax it to life, but I guessed she was all worn out, too, and she knew it was too late to save either one of them. Such were the thoughts that passed through my mind according to an entry in my old diary.

For the rest of that month, life on the sideroad continued as before but I never forgot that warm afternoon when I heard the sorrow in Mom’s voice. I don’t remember where Jude was, but I know she was too pragmatic to have bothered with tears. All these years later, I can almost hear her say, “For crying out loud, you two, it’s only a dead calf and cow. Why all the fuss?” Then she would have helped with the burying, gone in the house, made a baloney sandwich, and sang along with Elvis.

Such are the memories of one dog day in August when I was young.