When I was a kid, the Lenten season was a scary, somber time. Fear started on opening day when the priest ground ashes into my forehead, made the sign of the cross, and told me to remember that I was dust and unto dust I would return. Mom probably walked with us to the front of the church when we were very young, but by age seven we were on our own. Although I didn’t keep a record of my feelings, I’m fairly certain I didn’t want to think about death and dust. I wanted to play with my dolls and be happy, but that black cross was a reminder I’d better be good or I was headed for hell.

Hell was as much a part of my youth as was the Baltimore Catechism. Our priest arrived in Brimley when I was eight years old and departed ten years later. Throughout my childhood and teenage years, that priest and the catechism represented God and He was portrayed as a hard taskmaster. Our church had so many rules and regulations, it was a full time job just trying to avoid sin.

As a youngster, I was devoted to God because I was afraid of Him. Every night I knelt by my bed and said my prayers. I asked God to bless everyone, even the kids and teachers I didn’t like. I said prayers of Indulgence to help get my grandparents out of purgatory if that’s where they had landed. I said the rosary. I baptized my dolls. Although that was probably against the rules, the Baltimore didn’t mention it one way or the other so I was willing to chance it. I wanted my dolls to accompany me to heaven.

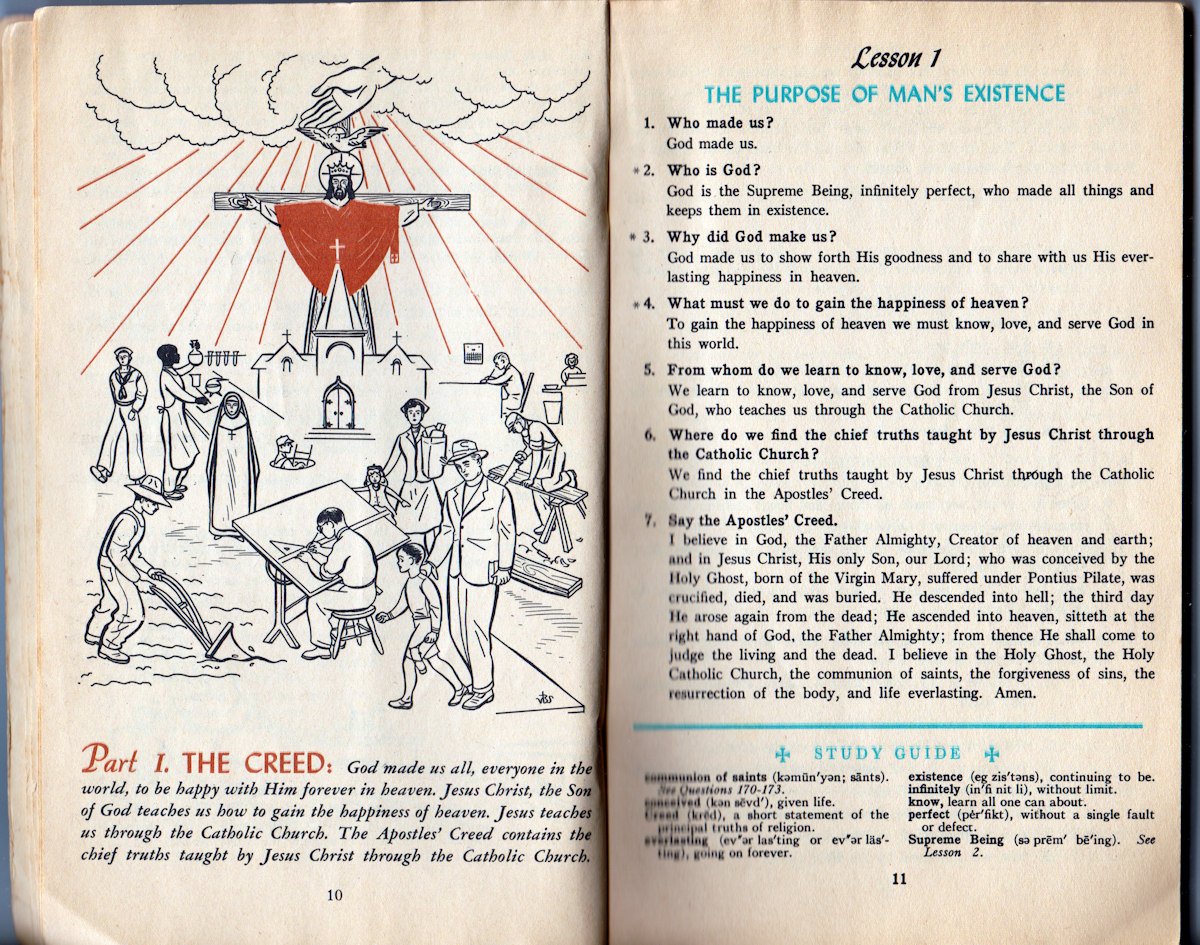

I knew nothing about Protestant religions and had no idea what they taught, but I was certain of one thing. The Catholic Church knew all the answers to life, death, and the hereafter. Everything was simple. I learned by rote the responses to such philosophical questions as who God was and why He made us. No problem. “God is the Supreme Being, infinitely perfect, who made all things and keeps them in existence.” He made us “To show forth His goodness and to share with us His everlasting happiness in heaven.”

But getting to heaven was easier said than done. It required a lot of work. During Lent it meant giving up candy. During the rest of the year, I didn’t have to “give up” anything, but I had to be obedient in thought, word, and deed. If I slipped up, hell loomed and it was no laughing matter. I remember a Friday in Lent when I forgot it was Friday and made a baloney sandwich. Apparently nobody was around to remind me I might be committing a mortal sin. As soon as I realized what day it was, I spat out the lunchmeat, fell to my knees, struck my chest three times, and begged God to forgive me. That’s how ingrained obedience was in my young brain.

Life was scary when I was a kid, but it was also uncomplicated. Father McGuire’s famous Baltimore II had all the answers, and I believed every one. At the time, I didn’t realize how lucky I was. If a question couldn’t be answered by our catechism, that was no problem. We were told to have faith, trust in God, and not get too nosy about things we didn’t understand. There was no such thing as questioning anything. Every summer nuns came for two weeks to supplement what our lay teachers didn’t know and what the priest didn’t tell us during his Sunday morning rants.

Would it have occurred to anyone to ask questions of a nun? Are you nuts? Those creatures clad in black and white were more terrifying than Frankenstein’s monster. We were country kids. We knew nothing except obedience and silence. I remember one time the priest stopped by when a nun was teaching class. I was in my early teens. When the priest walked into the room, everyone immediately stood as if God himself had entered. We were allowed to sit only when told to do so.

Something sticks in my memory about that day, and it has nothing to do with what the priest or nun said. Their messages fled like ashes in the wind. What I do recall is a peculiar feeling at the back of my neck. I ignored it as long as I could, then very slowly I raised my left arm and caught whatever was running around my collar. Without a wince or a word, I squished a spider between my thumb and index finger, all the time feigning interest in the words of our leader.

Something sticks in my memory about that day, and it has nothing to do with what the priest or nun said. Their messages fled like ashes in the wind. What I do recall is a peculiar feeling at the back of my neck. I ignored it as long as I could, then very slowly I raised my left arm and caught whatever was running around my collar. Without a wince or a word, I squished a spider between my thumb and index finger, all the time feigning interest in the words of our leader.

Fear, folks, is what kept me quiet. If a family of spiders had been building a web at the nape of my neck I would not have spoken one word. Fear of getting reprimanded by a Detroit nun or a fire and brimstone priest held my tongue. Can you imagine any teenager today keeping her mouth shut under similar circumstances? Fear of authority has vanished from the classroom, the church, the home, from everywhere.

And who knows? Maybe that’s a good thing. I only know that when Lent was over, I was glad. Easter Sunday meant purple shrouds covering the statues were removed, Thursday night Stations of the Cross were done with, Ash Wednesday’s cross was forgotten, and I could stuff myself with candy.

My Catholic roots have withered like last year’s windsaps, but the memories of the Lenten season when I was young remains as vivid as yesterday.

It was even more fun going to catholic school.We had confession once a month on the first Thursday,and trying at age 8,9,10,or even beyond was very difficult.Then during lent we were encouraged to go to communion.Only reason to go was we could then get chocolate milk ad a donut for a small fee for breakfast.

I am no longer a practicing catholic but some of those rules we had never leave you.

I find it interesting when people don’t understand the Church or her teachings they blame the Church. At 19 you were just ignorant of the Catholic faith.