By Sharon M. Kennedy

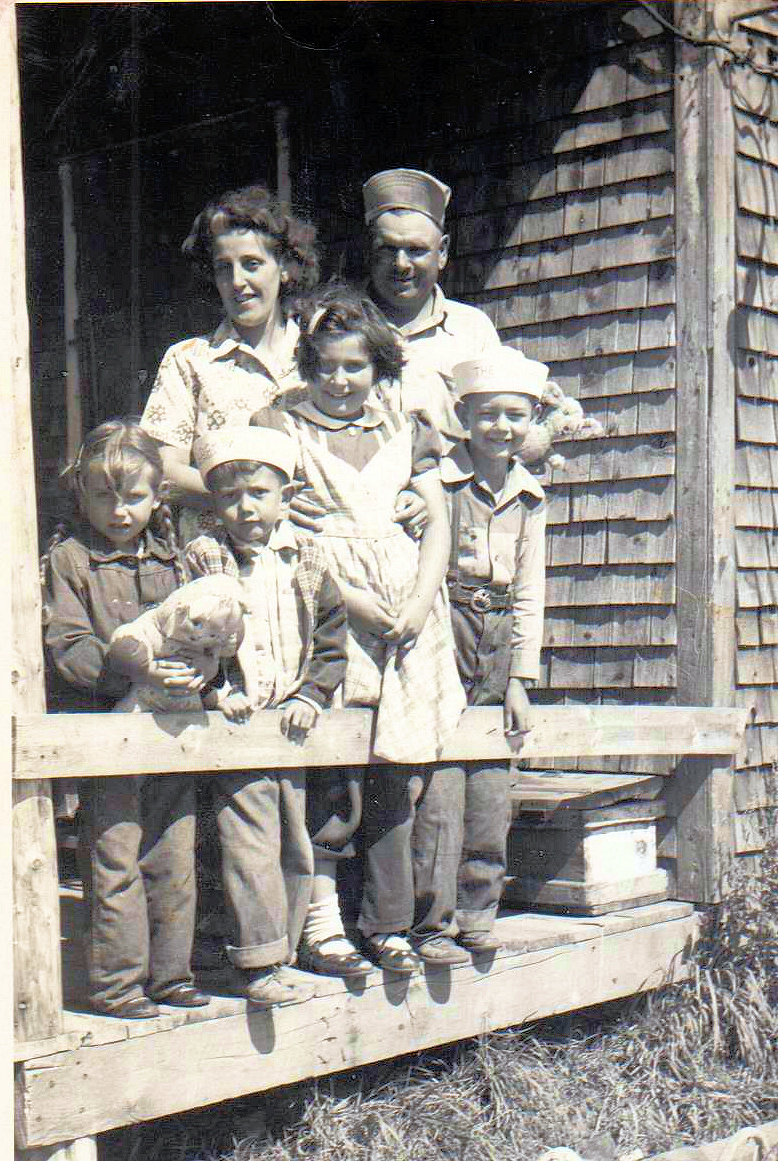

Mom, Dad, Jude, Sharon, and cousins

Mom, Dad, Jude, Sharon, and cousins

It’s been 39 years since we lost Dad. Some folks say a year is enough to mourn, but mourning is nothing compared to the memories. They never go away. They just creep into a far corner of your mind and wait until you grab a torn shirt hanging on a rusty nail or slip into a pair of old rubber boots. Then it all comes back, even to the familiar scent of Lifebuoy on a scrubbed neck or the honk of a Sunday morning horn saying, “Hurry up or we’ll be late for church.”

Memories of Dad are everywhere. I see him on the tractor as he plows the fields or in the barn as he milks the cows. But his fields are wild and overgrown now and the barn came down years ago, but no matter. There’s evidence of him from his tools and brown work gloves in the garage to an unopened box of milk filters in the wellhouse.

The chicken coop caved in, but I remember when I used to check for eggs. The coop always frightened me because it was low and dark. I was afraid Plucky might be setting and peck me. Then there was the time Dad ordered hen chicks and when they were older, they turned into roosters and chased me from the barn to the house. Dad scooped me up and held me until my tears stopped.

I remember the summer of 1977 when I came home. That was the year I spent waiting. I don’t know what I was waiting for, but I know Detroit faded into a whirlwind kaleidoscope behind me as I crossed the Mackinac Bridge and headed home. I returned to my parents and the farm where I had lived my childhood.

I was 30 then, had just turned 30, and maybe that had something to do with it. Who can explain the mysterious longing to return to a birthplace and to loved parents? Not I. Not then, not now, but I remember that summer as if it were yesterday. Everyone said I would find things changed and be disappointed and return to the city within a week. Friends wagged fingers and said vacation there, don’t move there. They preached and admonished and counseled, but I did not hear. I was heedless of everything except the need to return.

I found things much as I had left them. I breathed the stuff that had made me what I was, who I am. It was all there. Nothing had changed. Even the endless dust filling my nostrils carried an aroma all its own, and I knew just as surely as I knew I lived and breathed that I was home.

Mom and Dad were there, smaller than I remembered, more weathered, more gray, but joyous. Dad walked with a cane now, not a real cane, but a knotted tree limb he had worn smooth. Like the old house, he, too, listed to one side. He hobbled behind Mom, taking his time on the steps and keeping one hand on the railing. When I hugged him, I could have wept because he had grown old.

That evening I walked around the farm and saw washtubs full of rainwater and piles of rusty junk Dad was going to find a use for one day. I saw fences that were constantly being repaired now resting on the ground and wondered how many times Dad’s fingers had gotten caught on the barbs. I saw an antique cast iron tub that had been used as a water trough for the cows because the tub was handy and there wasn’t any use for it in the house because there was no bathroom.

I remembered the winters of my youth. Dad carried water from the wellhouse to the barn when the ground was too icy for the cows to walk to the trough, and he always leaned his head against the cow’s flank when he milked her. Sometimes I watched and wondered where he was. He seemed so far away. Once I thought I saw tears on his cheeks. I asked if he was crying, and he said no. I didn’t believe him then any more than I believed him when Gram died and he stood beside his mother’s coffin and the same phantom tears he denied were clearly visible.

Memories. They’re everywhere and just when you think you’re over them, you realize you’re not over anything. You long for just one more minute, one more second to curl your arms around your Dad and tell him you love him. Just half a second. Just any time at all. Then you pull yourself together and get on with your work, work of any kind to take your mind off the memories.

And yet you can’t help but look up and hold your head still and listen as if in the distance you hear the clang of a cowbell and you wonder if maybe, just maybe, Dad’s calling the cows home one last time. You run towards the barn, run past the heaps of junk, past the wellhouse, past the cat sunning itself, past the rotting fences. You open the barn door and close your eyes and wait and wish and hope with all your heart, but as you choke on tears, you know it was only the wind you heard carrying memories of long ago.

Be good to your father. You’ll miss him when he’s gone.

Sharon,

Have to say that I haven’t read many of your articles, but the photo stopped me in my tracks! Wonderful picture. And I just had to let you know that your parents were always kind to me.

You are a gifted writer!